|

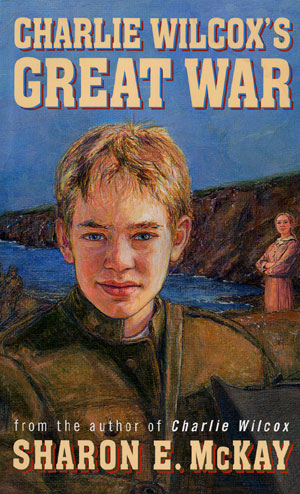

Charlie Wilcox’s Great War The year is l918. Charlie Wilcox, now seventeen years old, tall, broad and mature beyond his years, returns home to Brigus, Newfoundland. He is a man now, his childhood left behind on the battlefields of France and Belgium. And he is burdened by a secret, one he fears will inflict terrible grief on the village and people he loves – people who have already suffered so much because of the Great War. Then there is Claire. The girl he left had eyes like pies and a face like an egg. But the young woman before him is a beauty – and she is angry. Claire Guy wants answers. Charlie Wilcox’s Great War is the unforgettable story of a boy’s quest to find his courage and fulfil his destiny – a destiny hard-won on the great battlefields of Europe. But was the cost too high?

|

Charlie Wilcox’s Great War, Penguin, 2002. Review from Books in Canada, Summer 2003.

This is a sequel to Charlie Wilcox, Sharon E. McKay’s celebrated novel (three awards and a Governor General’s Award Nomination) about a 14-year-old from Brigus, Newfoundland who plans to stow away on a sealing ship and ends up on a troopship headed for England and the trenches instead. Either as a sequel or on its own, Charlie Wilcox’s Great War is an outstanding success. McKay tells the bulk of Charlie’s story through his own recollections, once he’s safely home again in l919. The novel opens as he lands in Brigus after three years away and begins to pick up the threads of the old life. But he has changed, thinks Claire, the girl whom he left behind; he is “older in his heart somehow.” As they struggle to reconnect, her need to know about war meshes with his need to unburden his heart, and over the course of a long afternoon, he tells her his story. It’s an epic story that’s also touchingly human in its graphic detail, fleeting friendships and innate responses to danger. One memorable example is Charlie’s unscheduled flight over occupied France in a two-seater biplane piloted by teen-aged, toffee-nosed twit. They are, of-course, shot-down, and manage a hair-raising and hilarious escape with the help of two friendly barmaids. Outrageous as this adventure may sound, its par for the course in Charlie Wilcox’s Great War. But even for a teenager war can be hell, a fact which McKay’s overriding message makes clear. Her hero survives, but several of his comrades do not. And falling sick while in the trenches, or hoping to stay alive until nightfall while hanging on the barbed wire in No Man’s Land, are experiences no human being should have to undergo. Charlie Wilcox finds his courage on the battlefield, but no one who reads this fine novel will want to go and do likewise.

|

|